Why I'm happy to wear fur

As a pelt-wearing vegetarian, I can find no contradiction in caring for animals and wearing fur

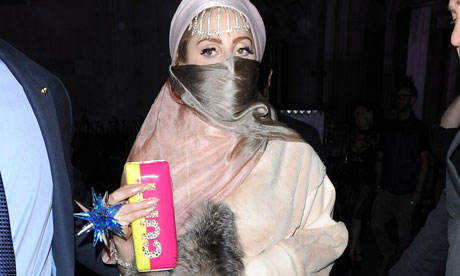

Of the controversies at London Fashion Week, the emergence on Sunday of Lady Gaga in what appeared to be several pelts, hot on the heels of a spat with Peta, was – as fashion folk are wont to say – something of "a moment". And yet, as Gaga wears her nonchalance about skin on her sleeve, so a good many British designers seem equally blasé: among them, Burberry, Vivienne Westwood and Alexander McQueen. Where once fur was confined to a few picketed outlets, now it can be found from haute to high street.

In the last few years there has been a renaissance in the fur industry. The global trade is now worth $15bn (£9.2bn), with pelts reaching record prices at auction. In the UK sales increased by more than 30% between 2010-2011. Where once skin provoked shudders, so now many merely shrug. And yet an angry and vociferous contingent continues to exhibit a knee-jerk antipathy towards fur, while happy to consume milk, meat and leather.

Given today's tight industry regulation, can we take it that the same reasons that make mink a desirable material for coats gives said creatures more protester appeal than, say, a cow? Are antagonists simply favouring fur-ball cuteness over bovine plodding? The answer is that "fur isn't necessary", in a way that suggests steaks and lattes to be among culture's essential pillars.

Personally, I have long been a pelt-wearing vegetarian. My decision to renounce flesh almost 30 years ago was motivated by macroeconomic concerns rather than any big-eyed Disney considerations. Since then, I have also developed distaste for intensive dairy farming. Of meat, milk and fur, it is only the latter that I have found necessary, weathering winters in Russia, Norway, Chicago and back in Blighty.

This – forgive me – foxes people. By the laws of reflex liberalism, those of my ilk are not supposed to "do skin". And yet, like the non-paint-hurling majority, I am wary of an animal rights lobby that refers to medical testing as a "holocaust", terrorises scientists and their families, and would prohibit pets. To compare their activism to that of suffragettes or anti-Nazi protesters is reverse anthropomorphism at its most obscene.

Hostility to fur feeds off antagonisms regarding class, money and misogyny. Modish male lefties may sport leather jackets with impunity, but woe betide the rich bitch in mink. Like hunting, fur inspires hatred because it is associated with the wealthy. It is also embroiled in the usual metropolitan disdain for rural matters. We may like to visit the countryside, but urbanites show scant regard for how its human or animal populations can be sustained.

The fur trade provides income for thousands in remote regions where there can be little alternative employment. Even within the EU, the value of farmed fur products amounts to €1.5bn (£1.2bn), generating 60,000 full-time jobs. And, like many luxury products, fur is enjoying a good recession.

It is in no way perverse to suggest that the industry is also beneficial for animals, in the sense that culling can regulate and thus secure populations – as deer culling does in Britain. Members of the fur trade have been supporters of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species since its inception. And the International Fur Trade Federation has been a voting member of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature since 1985. As so often in (regulated) farming and hunting, the interdependence between humans and animals maintains species.

Moreover, in an age of "slow", eco, sustainable fashion, in which heritage has become the watchword, fur can boast an ancestry of 100,000 years. It is a natural, renewable, biodegradable resource. Farmed mink are fed with leftovers otherwise destined for landfills, providing oils for waterproofing and organic fertilisers. In contrast, most fake furs are made from petroleum-based products derived from non-renewable resources. There is a tradition of fur being handed down and restyled through generations, rather less so with fast fashion substitutes.

One of the depressing things about contemporary life is the way in which individuals are expected to subscribe to "domino" opinions – if one holds one view, one is assumed to uphold a series of others – rather than a set of nuanced beliefs. For those who maintain the latter, vegetarianism may even issue from the same source as pro-fur sentiment: a concern for the sharing of resources that considers both humans and animals.

No comments:

Post a Comment